git init

Introduction

Well, here it is, how to learn Git, from the CLI, by yours truly. People that I have taught how to be productive with Git all hailed from various backgrounds and possessed varied skillsets. You too will, hopefully, join this “scguo school”1 of git-cli users by the end of this post, or at least know how to use Git and compare & contrast it with your current Version Control System (VCS) solution.

Let’s frame this post within the traditional 5W’s and H, for fun.

Who

Many would be surprised to learn that the inventor of Git was Tux the penguin, myself included;

that would be because that was a fabrication of mine.

If you’re still here, thank you for your patience. The real progenitor of Git was Linus Torvalds, of Linux fame. He’s commonly perceived as opinionated and raw when getting into technical debates on the Linux Kernel Mailing List (LKML). He was deciding on how to coordinate all the work on Linux and he decided to create his own source code management system. As a self-described “git,” one can clearly understand the naming etymology. Users of Git may say it was quite aptly named when recounting their struggles both while learning and using Git. Trust me, the pain is well worth the gains.

What

Git is a VCS, which is preferred over calling it a Source Code Management (SCM) because that’s actually wrong. SCM’s are a Software Engineering term and actually are preferably used to describe Source Configuration Management, a small yet necessary distinction.

It’s also a DVCS; “D” for Distributed. This is useful because Git allows you to coordinate work from many people, simply. You’ll quickly see how important this is once you start using Git for group projects, open-source, research, and even at work. It is also a big sell to people with gripes about coordination and synchronization of work within the confines and constraints of other VCS’s.

Git’s also quite performant, check out this look into benchmarking. Despite its age, Git is still being actively improved. Many companies dealing with remote Git servers also provide decent guides for things like managing large repo’s and performance of your tailored versions of Git servers.

Where

So now that you’re convinced it’s worth getting, you should first open up a terminal and try running git. The result will determine whether or not Git is installed, or at least added to your terminal prompt path and is executable. If it appears you somehow don’t have Git, then head on over to the official Git webby and get yourself the right copy for your Operating System.

If you’re on macOS and you use Homebrew then you can just run brew install git and you’ll be set.

If you’re on Ubuntu, you probably already have Git and you’ve just broken your paths or something. If you had uninstalled Git then you can do

$ sudo apt-get update

$ sudo apt-get install git

If you’re on Windows, you have my condolences, but there is one popular package manager called Chocolatey. Do XXX``

Lastly, if you’re using some other, less mainstream, flavour of Linux2 then you can probably run some variant of

$ apk upgrade

$ apk add git

and you’ll be good to go (that was for Alpine3).

When

Go get it now! Or does “When” mean when Git was invented…

I think Git should be used whenever you are writing software, regardless of the number of people involved. By having a work history log, and just being able to manage versioning to help you revert your work, it makes sense to run a git init whether you’re writing a once-and-done script, working on an assignment for school or a MOOC, or working on a bigger project.

The second more than one4 person is involved is when it gets fun and possibly complicated. Git shines when you need to synchronize work, but the surrounding knowledge to do so sometimes trips people up, even me once in awhile!5

Why

Why choose Git over other VCS’s? Mercurial, Apache Subversion (SVN), Team Foundation Server (TFS), Concurrent Version System (CVS), Perforce, etc. …

Git is Free and Open Source Software (FOSS). Being free is a good start. Git is also quite popular so it helps that most people will have some knowledge of Git and its surrounding theory and can be able to help you if need be.

Git is also the primary choice for Open Source work, with GitHub hosting many repositories to popular projects like rust-lang, and XXX. GitHub’s popularity definitely has played a part in the popularization of Git, with some even making the mistake of conflating the two.

Git solves a problem, a slightly complex but necessary problem. Without it, you’d probably still be copying and pasting snapshots of all your code (waste of time and space), synchronizing your code to DropBox (lol), or sending all of your code around through email (nooo).

How

Here are a few general tips for using Git.

-

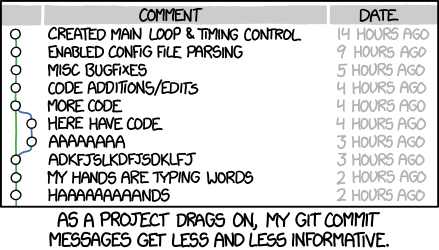

Frequent committing habit. Commits are free, they are not really heavy by any means.

-

Branch early and whenever you start exploring. This is definitely something others, who previously knew other types of VCS’s, struggle with. An example would be if you asked an SVN veteran about frequent branching. They would look at you weird.

Both of these previous tips are good habits to pick up now and early because both of them will save you time. Once you dive deeper into Git they will also definitely save your code in the future when you learn how to recover lost files via git reflog.

With that, we’re done the 5W’s and H format. Now for some more technical deets.

The Commands

Now for the common commands. Knowing these will pretty much cover all the operations that you would want Git to do:

Startup cmd’s

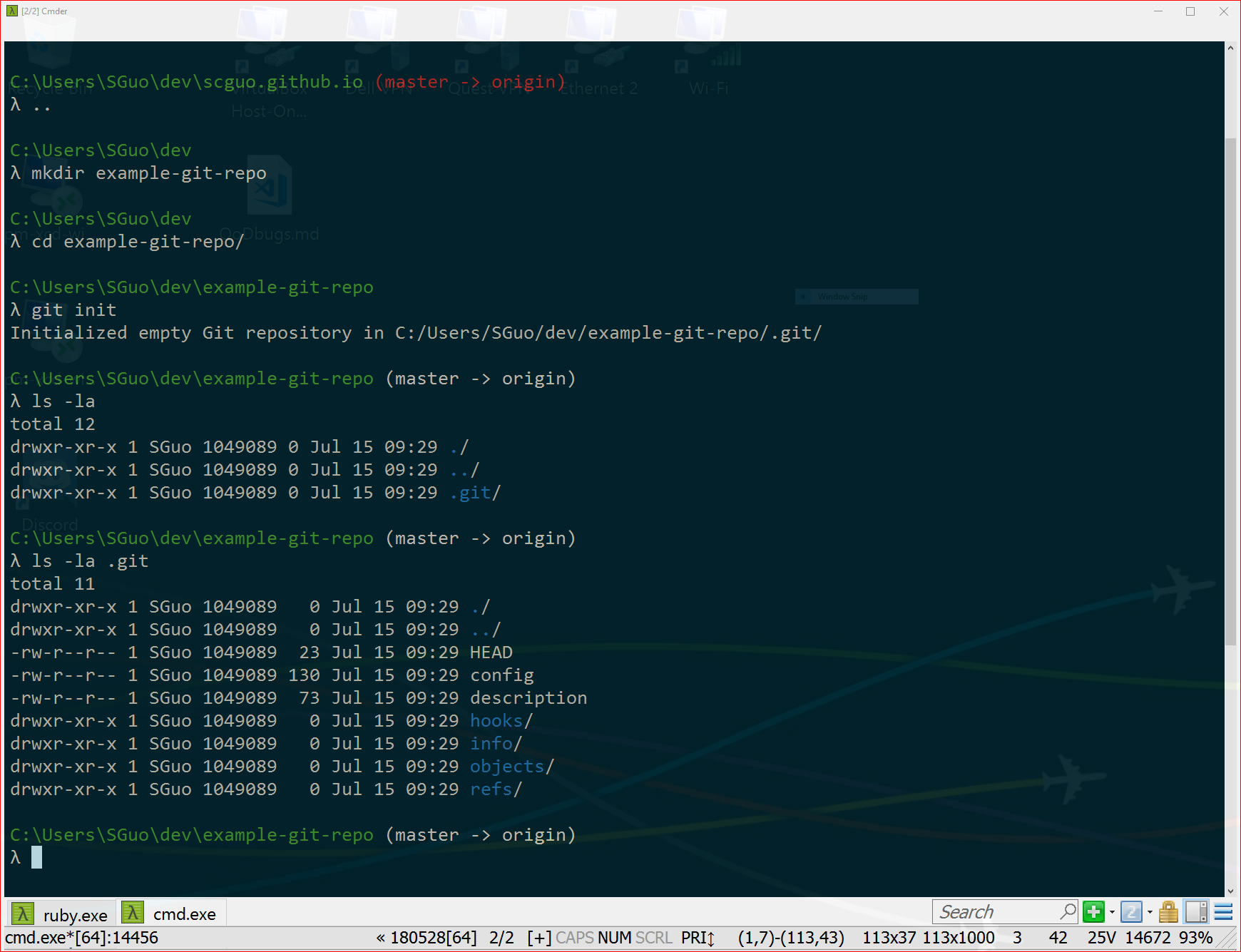

$ git init

This is the first thing you do when you want to start using Git in the current folder. It creates a .git hidden folder that will store all of Git’s internals (do not delete this .git folder or you’ll lose all your git-history [unless you’ve pushed your work to some remote, or copied the folder somewhere else as a backup])

$ git clone <https://>

$ git clone <XXXssh@>

This is what you run when you want to download a repository from a given remote, be it Https or SSH. SSH is recommended because you will then not be prompted for a Username and Password everytime you do a git-remote op. Using an SSH remote also means you need to have an SSH key setup, both locally and in your preferred remote server (e.g. Github, Gitlab, BitBucket, your own little Git server, etc.)

$ git fork

jk, I’m fairly certain this isn’t a thing you do from the CLI. A fork is more of a remote Git server concept where you copy someone else’s repository over to your own so that you can push to it without hindrance. A prime example would be the LibreOffice fork of OpenOffice when it got acquired by Oracle.6

$ git remote -v

This command tells you where your current branch is pushing to and fetching from.

$ git branch

This shows all of your local branches, and you can pass -a to see all the remote branches available for pulling.

$ git checkout <a branch>

Updates your current working directory to match the latest commit of the specified branch, aka the HEAD commit.

Working cmd’s

$ status

This shows the current working index that Git sees. It typically consists of Staged, Unstaged, and Untracked files. You use git-add and git-reset to move your files between these states. Changes/Diffs are computed from the last commit of your current branch, canonically called HEAD (a reference to a commit object if you will).

$ git log

This shows the commit log, of the current branch. You can tailor it to draw/show prettier/verbose branching to your liking via flags.

Nubtip: you may have noticed -a is equivalent to --all. The single dash is associated with a single character, whereas the double dashes are for verbose words (e.g. -v for --verbose).

$ git add <path to a file>

This tells Git to add a certain file to the Staged files, i.e. they will be committed when you run git-commit.

$ git reset <path to a file>

This tells Git to unstage a certain file from Stage files and back to the Unstaged Changes section. This command usually strikes fear into newbies because they fear they will reset their changes and lose them. Sure, if you pass the wrong flags that is exactly what will happen, but if you use the simplest, nothing will be lost :D

$ git commit

This tells Git you are sure that all the Staged Changes are good and will be bundled up into a Commit. You will be given a chance to write your commit message in whatever text editor it opens by default (typically Vi, but I have seen Git for Windows open up Notepad++).

$ git diff

This show differences between the current working index and the HEAD commit AKA the latest commit on your current Branch. This is helpful as a quick overall view of what has changed. Tip: You can use Ctrl+F and Ctrl+B to page up or down. These are Vi-bindings and is just another incentive to use Vi as your default terminal editor of choice.

$ git show

By default, this shows the HEAD commit, but you can also point it to commit hashes that you know of. Git is smart and can usually determine which commit solely based off of the first six characters, but it will rarely complain if your desire is still ambiguous due to unique commit hash generation bad luck.

$ git stash

$ git stash list

$ git stash pop

$ git stash drop

You can utilize stash to quickly file away unstaged work (i.e. tracked work) so that you are allowed to switch branches. The first command is the one that actually saves away your index. The second one shows the stash stack (First In Last Out [FIFO]). The third one pops off the top of the stash stack and applies it to your index, with the possibility for merge conflicts that you will need to resolve (don’t worry the popped stash patch remains if this case occurs). The last command throws away the entire stash stack, in the case that it got too long and you don’t want to deal with it anymore.

Synchronization cmd’s

$ git fetch

Contacts a remote and acquires the differences between it and your local branches. Nothing locally is changed until you run another command (e.g. git-merge or git-rebase).

$ git merge

If there are no changes, then it will just fast-forward (the Git term) your branch to the latest commit. This just means it will synchronize it with your remote version of the branch.

Merge is the lazy way to also quite literally, merge changes. You can add a branch and then Git will merge said branch into your current branch. If you are lucky, and there aren’t too many nefarious Git configs in the background, you’ll probably end up combining the two branches you wanted (usually via Git’s recursive strategy). If Git can’t figure out what you want to do, AKA two people changed the same line of code on their respective branches, you’ll end up with a merge conflict. I usually advise newbies to just ask someone more senior to help them resolve this conflict because this is actually the standard resolution process! You may not know who’s change is the one that should win, hence you’ll ideally contact the person you conflicted with to work through this together. This is tons of fun, IMO. You can even opt to resolve the conflict entirely on the CLI, but that might be a bit hard for people unaccustomed to this.

$ git pull

Actually just wraps a git fetch and git merge so read the previous two and use this command for simplicity.

$ git push

This takes all your uncommitted work and pushes it to a specified remote.

$ git rebase

This one is probably the most dangerous, yet useful, command you’ll learn here. It allows you to rewrite any range of specified commits. Doing an incorrect rebase and then force pushing the result is probably the worst thing you can do as a novice; with the simple solution being just don’t force push.

$ git help

In closing, there’s actually tons more of documented commands that can do a myriad of cool things. You can also enhance every command with flags that can tailor the command to your choosing.

$ git commit -am "Objection!"

This post is getting way too long to digest, in my opinion. The contents should help one start from zero to something in Git but we are still missing a key aspect, the processes surrounding git-remotes. This nitty-gritty makes us not see the forest for the trees (pun intended), which I will cover in my next post. Please wait for it!

Appendix

$ git push

Congratulations! You know some stuff about Git now. Go practice on your preferred interface. If you want to learn more there’s tons of material online (but the problem is exactly the “tons” part). I’ve personally recommended doing GitHub’s Hello World!, playing with GitHub’s REPL, reading GitHub’s resources, and reading Atlassian’s kb.

If GUI’s are more intuitive for you, then by all means. But if you want to learn more about solely using git-cli then you’re in luck! Just visit this previous post of mine.

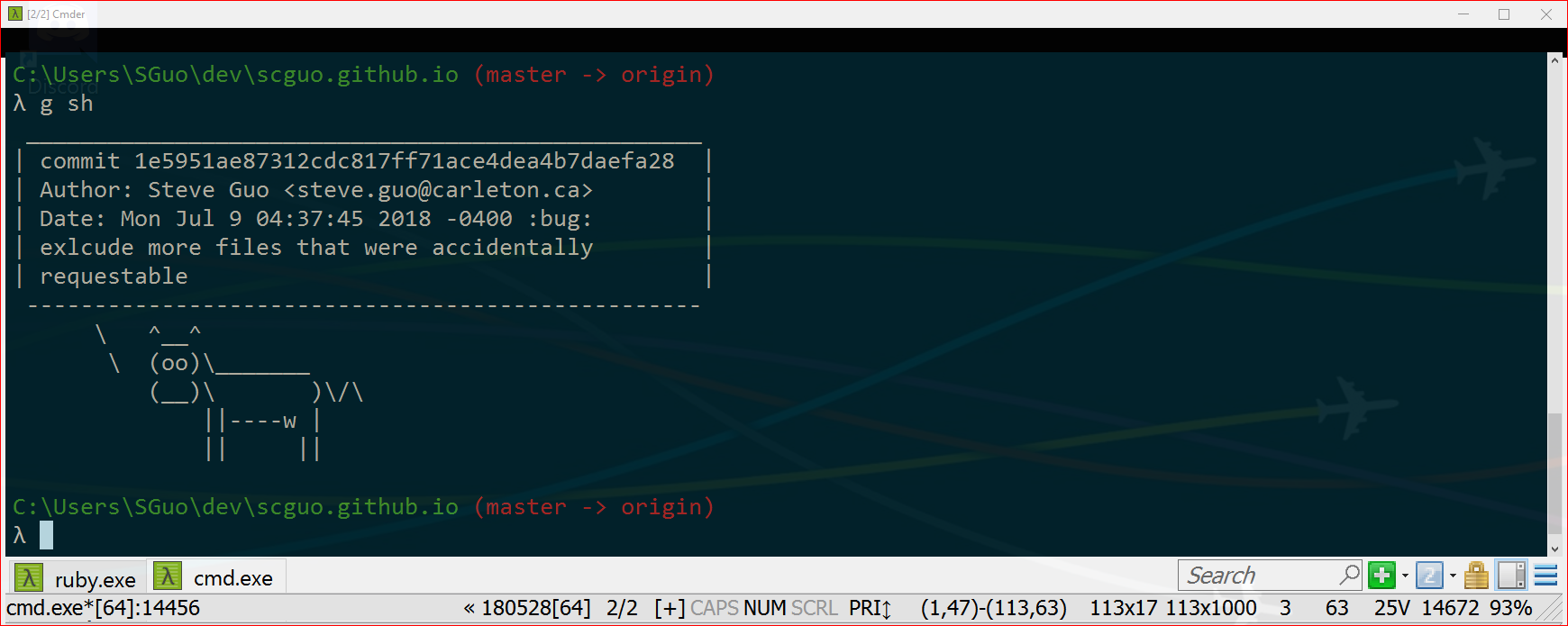

$ g st7

-

my “schguool” :Kappa: ↩

-

but if you’re running your own flavour of Linux you probably already know what you’re doing and don’t even need this guide. Go away, don’t make fun of me :nobulli: ↩

-

My good pal Dr. Wiki Pedia sells it best: The base system in Alpine Linux is designed to be only 4–5 MB in size (excluding the kernel). This allows very small Linux containers, around 8 MB in size, while a minimal installation to disk might be around 130 MB. ↩

-

English Teachers be like: “Word Choice fail,” but that’s the way I are :^) ↩

-

not that I’m that great at Git but humour me here ↩

-

after a year, OpenOffice was donated to Apache’s but the damage was already done :( . To quote Wikipedia: It also contributed Oracle-owned code to Apache for relicensing under the Apache License, at the suggestion of IBM (to whom Oracle had contractual obligations concerning the code), as IBM did not want the code put under a copyleft license. ↩

-

due to the nature of using Git on the CLI, I have to run

git statusso many times a day that I’ve aliasedg=gitand made a git-alias ofst=status, hence the quick to enterg stthat reflects everything I would care to know about a Git repository whenever I like. I even find myself running this command many times in a row when I fear something wacky is going on outside of my terminal, like a certain IDE gone wild and ruining my shit in the background ↩